Wait a second, Jason

The post-neoliberal turn in political economy is a valuable and transformative shift in economic policymaking

This week, with the basic institutions of our democracy under threat, Harvard economist Jason Furman published an essay entitled “The Post-Neoliberal Delusion: And the Tragedy of Bidenomics.”

The 5,000-word piece is an indictment of the ideas which have driven progressive economics over the past several years. This is not an abstract topic for Furman, who as the Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) under Obama, developed a first-hand sense of how economic policymaking is done in Washington. Over the course of his eight-year White House tenure, he became a mentor and confidante to many of the people who would later become Biden officials.

In the years since he was in government, Furman has burnished his reputation as one of the smartest, most talented economists in the country. He teaches the world-famous introductory Economics course at Harvard. His analysis is often critiqued from the right and from the left—a good sign that he is eminently reasonable, even-handed, and thoughtful.

So why write a takedown of Bidenomics, the work of his former colleagues, friends, and mentees, and the economic accomplishments of the past several years? And why now?

Ever since Trump’s first victory in 2016, there has been a simmering war of ideologies raging inside the community of individuals who work on political economy. That is now coming to a head. As the world focuses on the wrecking ball of contemporary Trump’s policies, behind the scenes, centrist and left-leaning economists and policymakers are taking out their knives in an effort to define what makes for “reasonable” economics in the years to come.

Inevitably, the debate is getting personal, because the implications for the future of economic policy are profound. Should the institutions of democracy endure and Democrats return to power, which conventional wisdom about economic policymaking will dominate? That’s not a knife fight in the faculty lounge; it’s a struggle to recast the economic foundations of American democracy.

One understanding of political economy—the one Furman doesn’t like—is ascendant. By employing tools like public investment, competition policy, and smart regulation, policymakers can shape economic outcomes to meet political goals like combating climate change or supporting chip manufacturing. This Hamiltonian vision believes government can guide the economy toward certain outcomes, weighing the trade-offs between social and political goals with the need for economic efficiency and overall growth. Bizarrely, many Trump economic officials and Biden folks share that approach, even if they diverge dramatically on the goals.

That’s a disruptive set of ideas. The sooner they can be extinguished, Furman believes, the sooner we can return to Clinton- and Obama-era economic orthodoxy. That would be a mistake.

The Furman Story

According to Furman’s story, the tragedy of Bidenomics begins with the rise of a new set of policymakers influenced by “post-neoliberal” ideas, as he calls them. One former colleague in particular, Brian Deese, led a team at the National Economic Council (NEC) that developed new policies that contradicted the orthodoxy that Furman and others enshrined in the Obama years. A new generation took over economic policy and threw the sacred texts of neoclassical economics out the window, Furman contends.

They pursued experimental ideas long out of favor, including:

prioritizing full employment over other economic goals

crafting industrial policy to support infrastructure, climate investment, and semiconductor production, and

reinvigorating antitrust enforcement to confront corporate concentration.

According to Furman, these “heterodox” ideas did little (no?) economic good and contributed significantly to the inflationary surge that cost Joe Biden the election.

The implication is clear. If only Furman, presumably alongside people like former Treasury Secretaries Larry Summers and Robert Rubin, had been at the helm, we would have avoided all of this nonsense. Judicious and empirical, these real economists would have thought in terms of market failures, econometric models, and trade-offs. If Biden had listened to the traditionalists like Obama did, he’d probably still be President, Furman implicitly argues. (One assumes Biden’s approval ratings would have been higher, dissuading him from dropping out of the race.)

Over the past few days, many of Furman’s core empirical claims in the essay have been carefully considered and refuted. The writer Noah Smith—who has ironically made a reputation of criticizing much of Biden-era economic policy—made an inventory of the most spurious and forced of Furman’s arguments.

The national debt as a percent of GDP did not in fact grow meaningfully under Biden.

Labor force participation ticked up and unemployment fell, remaining near historic lows despite a rapid rise in interest rates.

Domestic investment spurred a construction boom.

No other advanced economy recovered from Covid as well as the American one.

Only 1-2 percent of the inflationary surge was likely explained by the Biden stimulus package.

Furman’s friend, Jared Bernstein, the former chair of the Biden CEA, corrected more claims.

Median workers’ real wages did in fact grow during the Biden years

The Biden administration permanently expanded the food stamp program and Obamacare registration.

Their posts are full of graphs, stats, and all the details.

We all have our biases. But particularly in this moment, when rhetoric, divisiveness, and hot takes are so pervasive, we have to challenge ourselves to think more carefully. It’s a good sign that Smith and Bernstein, despite their sharp disagreements with the latest article by Furman, both made it very clear that they continue to respect him as an economist and an interlocutor, as do I. Bernstein goes further and willingly admits to mistakes in the Biden period. That kind of humility and willingness to engage in frank debate is what we need more of.

Post-Neoliberalism & Marketcraft

We will also need something more—something that neither Furman, nor Smith, nor even Bernstein seem to think we need: a frank defense of the emerging “post-neoliberal paradigm” or new economics. Not because Biden-era policies were perfect—as Furman himself claims to believe, we live in a world of difficult tradeoffs and second-bests—but because it represents a welcome sea change in thinking about how to make smart economic policy.

Beginning in Trump’s first presidency, and reinforced and expanded in Biden’s term, policymakers in Washington have embraced their power to manage markets toward political goals. They want to craft markets to serve the American people. They do not see themselves as market takers, but market makers.

The old set of ideas, shared by Reagan Republicans as well as Clinton and Obama Democrats, was oriented around a desire to enhance market efficiency in pursuit of economic growth. In this view, markets work well on their own when government minimizes “distorting” regulatory policies. Because Furman is a Democrat and not Republican, he genuinely believes in the need to correct for market failures by creating a strong safety net and progressive taxation. But in this story, government comes second after the market. The debate is over the amount of unemployment benefits or how high the marginal tax rate should be – not about the institutional structure of American capitalism in the first place.

Because of the rapid and influential growth of a new set of ideas in the late 2010s, many people, including myself, start from a different perspective. We watched the tepid recovery from the Great Financial Crisis, the growing and urgent threat of climate change, the rise of China, and the disruption of the pandemic. “Self-regulating markets” did not respond to these challenges, and the dynamism of American capitalism needed to be harnessed to meet the political challenges of the time.

Put simply, the new paradigm is grounded in marketcraft, a belief that our economy needs to be structured and managed to work the way we want it to. Americans don’t work for the economy; markets should work for us. This approach affirms the critical importance of the dynamism of American capitalism and endeavors to channel its energy toward public aims.

Americans don’t work for the economy; markets should work for us.

The difference showed up prominently in the Biden agenda. Biden-era policymakers believed that America would be stronger if we had a faster, more robust recovery from the pandemic, and they passed a major stimulus package to prevent the kind of tepid recovery that came after the GFC. (The plodding recovery from the GFC, we should not forget, became the political terrain on which Trump found a secure footing).

The Biden team believed that American should manufacture critical semiconductors in the United States for national security reasons and that public investment could guide the economy toward that goal. They believed climate change poses a profoundly disruptive risk to our way of life, so they moved to use public investment to speed the pace of innovation. The Biden team believed that when markets are competitive, they generally lead to lower prices, higher wages, and more innovation. So they moved to strengthen and empower institutions to enforce antitrust laws, enabling markets to be more competitive and open.

In all of these examples, public policy managed markets toward political goals; it did not just want to correct “failures” after they occurred. Now every major semiconductor manufacturer in the world is building facilities here, and TSMC is fabricating the advanced A16 chips that power the iPhone at its Arizona facility. Last year $272 billion was invested in climate technologies, up 24% year-over-year, despite Trump’s threats to stem the flow. The FTC under Lina Khan established new merger guidelines and created a drumbeat of victories to prevent further corporate consolidation.

These are old ideas made new again. Marketcraft predates neoliberalism by nearly a century and endured even in the heyday of Ronald Reagan, as my forthcoming book shows. Since the start of the Republic, there has been a community of policymakers pursuing this approach to economic policymaking – sometimes on the left, and sometimes on the right. Many of the efforts have been successful, and some have failed. We have a lot to learn from those experiences, which is why I wrote the book in the first place.

The point isn’t that the Biden administration’s policies were all right and perfect. They weren’t. The stimulus package was bigger than it should have been. The IRA needed a coordinating institution to make it work. Requiring chip makers to provide child-care centers was a symbolic but burdensome addition that slowed implementation by complicating compliance.

The most glaring oversight was the inability to clear out the regulatory morass that slows construction and development in the United States. We should be able to build semiconductor plants faster, install more electric vehicle charging stations, and complete infrastructure projects in a reasonable timeframe.

But where does the responsibility for the sloth of policy implementation lie? What would Furman’s vision have done about it? These are the critical questions that need consideration. As Furman himself freely concedes, neoliberalism “failed to deliver high levels of employment for prime-age workers in the United States for decades.” (emphasis added) We could make the political decision to run the economy well below capacity for another couple decades. But that wouldn’t be a solution to the problem of permitting and regulation—except in the sense that no one will even apply for building permits if there’s a depression.

We know what we need: an alternative to both chronic slack and the stubborn constraints which currently start to bind as soon as we approach full employment. Bidenomics did not solve this difficult, essential problem. But Biden-era policies represent real steps toward a strong, resilient economy, which we abandon at our own political and material peril.

Let’s be clear: Americans hated inflation. Rightfully frustrated with the high cost of living, voters blamed the incumbent in last fall’s election. If prices hadn’t jumped as precipitously as they did, voters may have felt less skeptical of a Kamala Harris presidency. The high cost-of-living remains a major problem for Americans, and it’s the one thing they’re already most frustrated with Trump about.

But Democrats lost the presidential election because Biden was an aging President who could not communicate with the American people by the end of his term, let alone convince them that he was fighting for them.

The counterfactual to consider is this: would Harris have done better, or worse, if the Biden administration had pursued the old paradigm policies that Furman suggests?

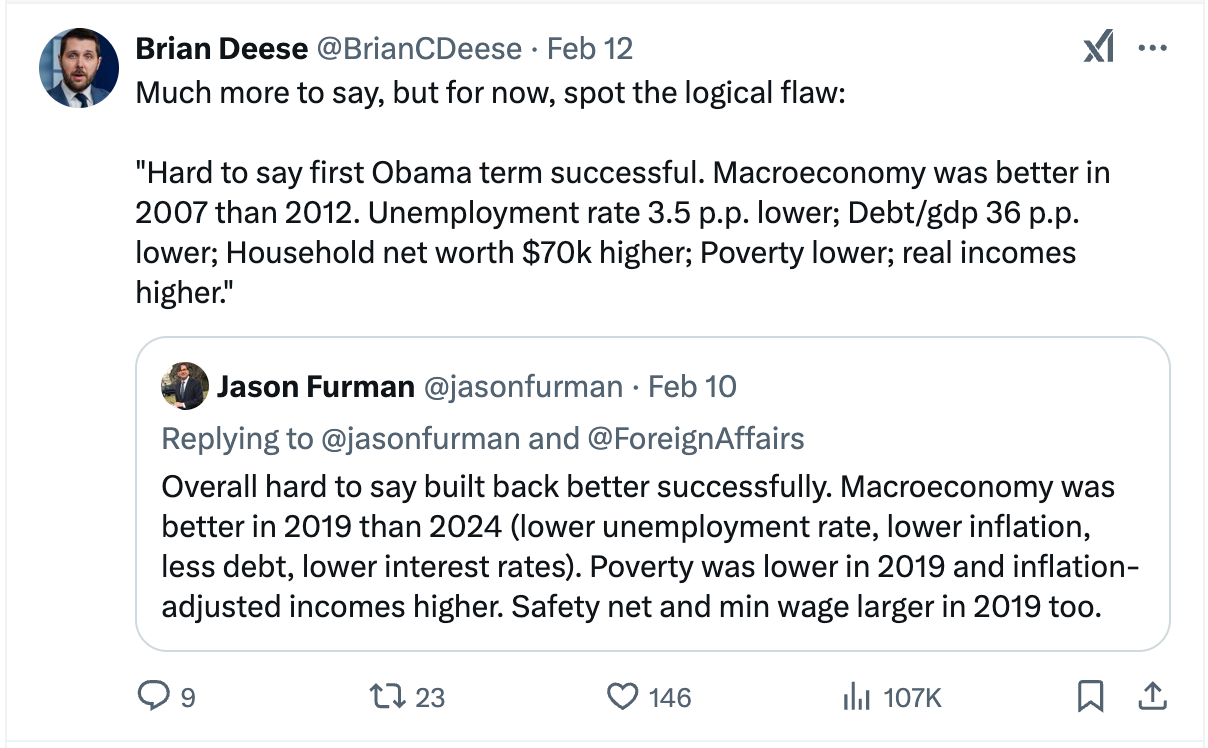

Deese suggested on Twitter that the record from the first Obama term is illustrative:

After four years of Furman economic policies (2009-2013), unemployment was higher (up to 8% from 7.8%), debt to GDP was higher (up to 100.7% from 77.1%), household net worth was flat, median incomes were down, and the poverty rate was up (15.8% to 14.3%). This kind of comparison is painfully artificial and rhetorical, but it’s the one Furman turns to in order to pan Bidenomics. It doesn’t reflect well on his approach in a similar post-crisis four-year period.

Furman, like many economists, loves to talk in terms of trade-offs and opportunity costs, because it’s a signal of the profession’s rigor. Biden-era policymakers shared a “broader unwillingness to contend with tradeoffs,” Furman claims. We’re supposed to believe that sophisticated thinkers don’t think in terms of right and wrong or good and bad, but rather who gains and who loses and how it affects a dynamic system.

For the research for my book, I spoke to many officials at the Biden-era NEC, Treasury, and Commerce, and virtually all of them were obsessed with the question of trade-offs. To take one telling example from the top, Biden explained the rationale of the size of his stimulus policy crystal clear: “The biggest risk is not going too big, it’s if we go too small.” Obviously, the optimal fiscal policy would be just right. But Biden and his team, operating in the world we actually live in, considered the options and made a tough choice.

When Furman says “you don't understand trade-offs,” is it just a slippery way of saying “I don’t like your conclusions?” There’s no utility to be gained in substituting magic words for honest debate.

Is it possible that Furman views these two seemingly throwaway paragraphs as part and parcel of "post-neoliberal economic policy" and not simply de minimis bumps to be sanded away?

"The point isn’t that the Biden administration’s policies were all right and perfect. They weren’t. The stimulus package was bigger than it should have been. The IRA needed a coordinating institution to make it work. Requiring chip makers to provide child-care centers was a symbolic but burdensome addition that slowed implementation by complicating compliance.

The most glaring oversight was the inability to clear out the regulatory morass that slows construction and development in the United States. We should be able to build semiconductor plants faster, install more electric vehicle charging stations, and complete infrastructure projects in a reasonable timeframe."

As far as regulations that slow building, not sure I'd call it an oversight, seems like it was identified and ended up being ignored, harder to characterize why it was ignored in some sense. My assumption was it was a combination of people thinking the tradeoffs were OK, slow building is fine, and leveraging any wanted regulatory policy change for other things.